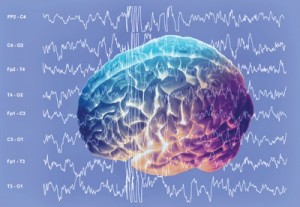

Brain Waves Create Internal Map of Our Surroundings

Electrical oscillations (rhythmic wave activity) in the brain may play an important role in our ability to navigate through the physical world and store memories based on this experience, according to a study at the University of California, San Diego.

The findings may help scientists understand the root causes of neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

In a certain part of the brain, neurons called grid cells actually create a kind of internal map of the outside world. To do this, they need perfectly-timed electrical oscillations from another part of the brain to serve as a sort of neural pacemaker.

“This work is the first to demonstrate that oscillatory activity has a well-defined function in brain areas that store memories,” said Dr. Stefan Leutgeb, an assistant professor of biology at UCSD who headed the team of researchers.

Components of the brain important for memory — the hippocampus and the nearby entorhinal cortex — are among the first brain areas to degenerate in Alzheimer’s disease, leading to problems such as memory loss and disorientation. These two brain regions house three kinds of neurons that help create spatial memories as well as the spatial information necessary for episodic memories of life experiences.

Leutgeb and fellow researchers measured the electrical activity of grid cells in rats that were prompted to explore a four-foot by four-foot area.

These grid cells, located in the entorhinal cortex, create and hold an internal representation of the external environment. This representation is a grid-like map consisting of repeating equilateral triangles that fill the space in a hexagonal pattern. As the animal navigates through its outside environment, a certain grid cell in its brain becomes active when the animal’s position coincides with any of the matching vertices in its “internal” map.

“Our findings represent a major milestone in understanding memory processing, and they will guide efforts to restore memory function when cells in the entorhinal cortex are damaged,” said Leutgeb.

Researchers would stop the oscillatory input by manipulating certain pacemaker cells in the brain; they discovered that this triggered a significant deterioration of the grid cells’ maps of the environment. Interestingly, brain signals that indicate precise location and also the compass signal were not disturbed during this process.

“It has been thought that the hippocampus is under control of the entorhinal cortex, so there was the assumption that grid cells would have a very large impact on place cells. We are surprised at how the function of place cells is maintained in the face of significant disruption in grid cell function,” said Leutgeb.

“This important result shows that, in general, you can eliminate a substantial amount of incoming information to a brain circuit without that brain circuit losing a majority of its functionality,” he added. “The implication of this finding is that restoring memory function does not require that we exactly reassemble damaged neural circuitry, rather we can regain function by preserving or restoring key components.”

“Our findings are a major step towards identifying these key components in an effort to preserve memory function in aging individuals and in patients with neurodegenerative diseases,” he said.

The research is published in the April 29 issue of the journalScience. Scientists from Boston University report similar findings in a companion paper in the same issue.

Source: University of California