Smoking’s Toll on Health Is Even Worse Than Previously Thought, a Study Finds

However bad you thought smoking was, it’s even worse.

A new study adds at least five diseases and 60,000 deaths a year to the toll taken by tobacco in the United States. Before the study, smoking was already blamed for nearly half a million deaths a year in this country from 21 diseases, including 12 types of cancer.

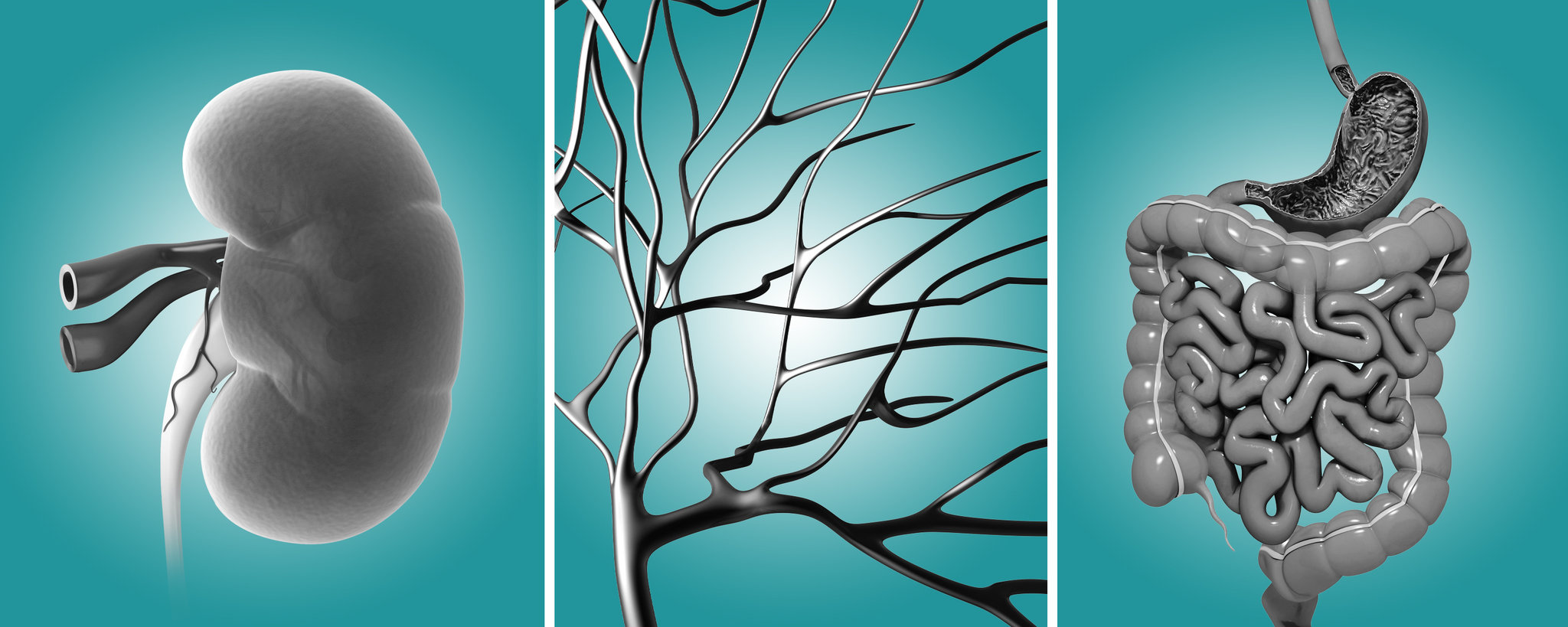

The new findings are based on health data from nearly a million people who were followed for 10 years. In addition to the well-known hazards of lungcancer, artery disease, heart attacks, chronic lung disease and stroke, the researchers found that smoking was linked to significantly increased risks of infection, kidney disease, intestinal disease caused by inadequate blood flow, and heart and lung ailments not previously attributed to tobacco.

Even though people are already barraged with messages about the dangers of smoking, researchers say it is important to let the public know that there is yet more bad news.

“The smoking epidemic is still ongoing, and there is a need to evaluate how smoking is hurting us as a society, to support clinicians and policy making in public health,” said Brian D. Carter, an epidemiologist at the American Cancer Society and the first author of an article about the study, which appears in The New England Journal of Medicine. “It’s not a done story.”

In an editorial accompanying the article, Dr. Graham A. Colditz, from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, said the new findings showed that officials in the United States had substantially underestimated the effect smoking has on public health. He said smokers, particularly those who depend on Medicaid, had not been receiving enough help to quit.

About 42 million Americans smoke — 15 percent of women and 21 percent of men — according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Research has shown that their death rates are two to three times higher than those of people who have never smoked, and that on average, they die more than a decade before nonsmokers. Smokers are more than 20 times as likely as nonsmokers to die of lung cancer. Poor people and those with less formal education are the most likely to smoke.

Mr. Carter said he had been inspired to dig deeper into the causes of death in smokers after taking an initial look at data from five large health surveys being conducted by other researchers. The participants were 421,378 men and 532,651 women 55 and older, including nearly 89,000 current smokers.

As expected, death rates were higher among the smokers. But diseases known to be caused by tobacco accounted for only 83 percent of the excess deaths in people who smoked.

“I thought, ‘Wow, that’s really low,’ ” Mr. Carter said. “We have this huge cohort. Let’s get into the weeds, cast a wide net and see what is killing smokers that we don’t already know.”

The research was paid for by the American Cancer Society, and Mr. Carter worked with scientists from four universities and the National Cancer Institute.

The study was observational, meaning that it looked at people’s habits, like smoking, and noted statistical correlations between their behavior and their health. Correlation does not prove a cause-and-effect relationship, so this kind of research is not considered as strong as experiments in which participants are assigned at random to treatments or placebos and then compared. But people cannot ethically be instructed to smoke for a study, so a lot of the data on smoking’s effects on people comes from observational studies.

Analyzing deaths among the participants from 2000 to 2011, the researchers found that, compared with people who had never smoked, smokers were about twice as likely to die from infections, kidney disease, respiratory ailments not previously linked to tobacco, and hypertensive heart disease, in which high blood pressure leads to heart failure. Smokers were also six times more likely to die from a rare illness caused by insufficient blood flow to the intestines.

Mr. Carter said he had confidence in the findings because, biologically, it made sense that those conditions were related to tobacco. Smoking can weaken the immune system, increasing the risk of infection, he said. It is also known to cause diabetes, high blood pressure and artery disease, all of which can lead to kidney problems. Artery disease can also choke off the blood supply to the intestines. Lung damage from smoke, combined with increased vulnerability to infection, can lead to multiple respiratory illnesses.

Two other observations supported the findings, he said. One was that the more heavily a person smoked, the greater the added risks. The second was that among former smokers, the risks diminished over time. In general, such effects, known as a dose response, suggest that an observed correlation is more than a coincidence.

The study also found small increases in the risks of breast and prostate cancer among smokers. Mr. Carter said those findings were not as strong as the others, adding that additional research could help determine whether there were biological mechanisms that would support a connection.

A 2014 report by the surgeon general’s office said the evidence for a causal connection between smoking and breast cancer was “suggestive but not sufficient.” The same report found no evidence that smoking causedprostate cancer, but it noted that in men who did have prostate cancer, smoking seemed to worsen the outcome.

The diseases that had previously been established by the surgeon general as caused by smoking were cancers of the esophagus, stomach, colon, liver, pancreas, larynx, lung, bladder, kidney, cervix, lip and oral cavity; acute myeloid leukemia; diabetes; heart disease; stroke; atherosclerosis; aorticaneurysm; other artery diseases; chronic lung disease; pneumonia;influenza; and tuberculosis.