Controlling Self-Awareness During Sleep

Most dreams occur during the rapid eye movement (REM) sleep phase. During REM, a sleeper is generally not aware she’s dreaming and experiences her dream as reality. This is thought to occur when certain parts of the prefrontal cortex—linked to awareness and higher cognitive function—are inactive. Some people also experience lucid dreams; they are aware that they are dreaming and may be able to modify their dreams’ outcomes. Unlike during REM sleep, parts of the prefrontal cortex have been previously shown to be active during the more self-aware lucid dreaming state.

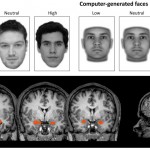

Psychologist Ursula Voss at Germany’s Goethe University Frankfurt and her colleagues have now linked neuronal activity in the frontal and temporal brain lobes with lucid dreaming. In a study published today (May 11) in Nature Neuroscience, they report having been able to induce lucid dreams by applying low-current stimulation to the scalps of volunteers who were sleeping.

“This is an exciting study that demonstrates causality,” said Ryota Kanai, cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Sussex in the U.K., who was not involved in the study. “When a certain frequency of electric current is applied to the brain, this study shows that lucid dreaming can be induced.”

The researchers applied mild current at different frequencies to frontal and temporal brain positions across the scalps of 27 sleeping volunteers using a noninvasive technique called transcranial alternating current stimulation. This stimulation does not disturb sleepers; it modulates the resting potential of neurons, but does not cause an action potential, according to study coauthor Michael Nitsche, a professor of clinical neurophysiology at the University Medical Center in Göttingen, Germany, who helped develop the technique.

All 27 study participants were selected because they had not previously experienced lucid dreaming. The researchers stimulated sleeping participants with currents after two to three minutes of uninterrupted REM, about half-way through the night. They repeated the double-blind experiments on the same sleepers for up to four nights. After each night’s sleep, the participants immediately filled out dream reports including a quantitative sleep-consciousness questionnaire.

The authors found that only stimulation at a range of frequencies between 25 Hz and 40 Hz—the so-called gamma frequency range—induced further gamma frequency activity in the frontal and temporal lobes. This gamma frequency activity correlated with lucid dreaming, as reported by the participants.

“I did not have much hope that this experiment would actually work,” said Voss. “For us, it was surprising that you can actually force the brain to take on a new brain rhythm—that the brain really adapts and the neurons begin to fire at the new frequency with just this mild stimulation.”

Martin Dresler, a neuroscientist at the Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour in Nijmegen, the Netherlands—who studies sleep-related memory but was not involved in the current study—was also surprised by the strong effects of the stimulation on the subjects’ consciousness that the researchers found. “It’s quite hard to get participants to a lucid sleep state in the laboratory,” he wrote in an e-mail toThe Scientist. “These findings are therefore very promising for lucid dreaming research in general, and for potential clinical applications.”

One potential application of this type of brain stimulation is to treat patients suffering from delusions and hallucinations. “The level of consciousness of these individuals may be relatively similar to those of healthy individuals in a REM sleep dream state in which the state seems to be reality,” said Nitsche. “Inducing what is known as a secondary mode of consciousness in which one is self-aware and capable of abstract thinking, may be useful for those suffering from altered reality states.”

Voss and Nitsche now plan to study the effects of these stimulations on waking people.

Dresler and Kanai cautioned that the long-term effects of even gentle electrical brain stimulation are not yet known. “It’s a controversial area, but it’s really exciting that it looks like it’s possible to induce lucid dreams by brain stimulation,” said Kanai.