Who You Are

New research shows that personality traits are mirrored by changes in our brains. These changes define who we are. To change your personality you need to reconfigure your brain!

Are you an optimistic person? Do you care about the feelings or wellbeing of others? Or do you sometimes seem withdrawn and notice the bad things going on in the world… We all have our “ups and downs” and the kind of attitude we have towards life defines our personality. But what exactly is personality? And can it be changed?

Right now, as you are reading this, your assessment of the external world is being processed and filtered by your brain. While the brain has often been compared to a computer, it really does not have software. Most of what you retain, manipulate and categorize from the outside world is the result of hardware — the neurons and their components are physically rearranged.

This means that the kind of personality you have right now is the result of certain unique configurations within your brain. Yes, personality can and does change over time, but it requires similar changes to the structure of your brain. I hope to show you how this can be achieved in this article.

What exactly is personality?

Psychologists have had tests to measure personality for decades. The behavior that we most often exhibit is called a trait. And, for decades, there have been as many traits as there are adverbs to describe feelings. But that’s changed now. Psychologists have rendered all of the possible traits down to five — The Big Five. And with this new approach to understanding personality has come the link between these five characteristics of personality and specific regions of the brain.

|

The Big Five — characteristics of personality:

|

In the martial arts there is a phenomenon called “muscle memory.” A particular movement is practiced again and again — in slow motion at first, but then at lightening speeds. Eventually, a complex thrust or a defensive move involving many precise steps is encoded in the body’s muscles where it can be executed perfectly without conscious thought. Our attitudes and emotions are like this also. We learn how to react to the outside world, often without having to make conscious decisions.

But what if our reactions are causing problems, like making is depressed or self-destructive? What if our personality keeps us feeling lonely or instigates conflicts with our family, friends or the law? Can anything be done?

I was watching a Steven Seagal movie recently and one of the antagonists in the film asked Seagal’s Kung Fu character,

“Inside of me there are two dogs. One of the dogs is mean and evil. The other dog is good. The mean dog fights with the good dog all the time. Which dog wins?” To which Seagal answers, “The one I feed the most.”

The wisdom in this riddle was recently demonstrated by a couple of scientific studies I think you need to know about.

The Dynamic Brain

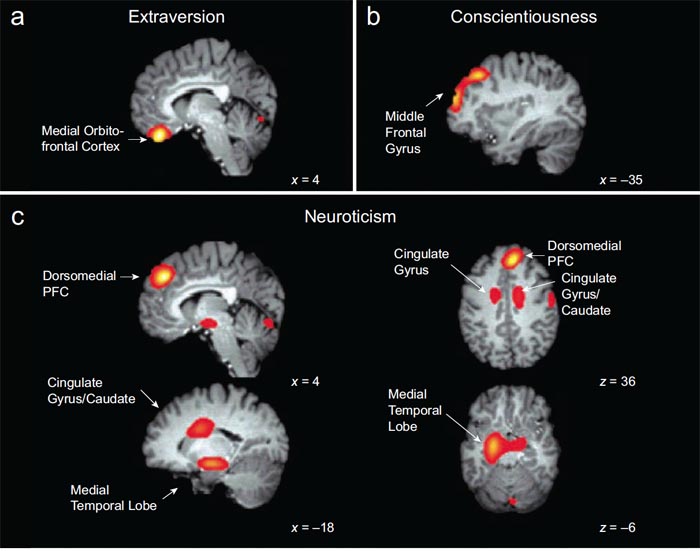

Colin G. DeYoung [right] of the Psychology Department, University of Minnesota, and his colleges, recently published the results a study they conducted which linked personality traits to changes in specific regions of the brain. The study found significant correlations of increased and decreased volume in parts of the brain associated with the “Big Five” characteristics of human personality.

Colin G. DeYoung [right] of the Psychology Department, University of Minnesota, and his colleges, recently published the results a study they conducted which linked personality traits to changes in specific regions of the brain. The study found significant correlations of increased and decreased volume in parts of the brain associated with the “Big Five” characteristics of human personality.

In their study, they had 116 adults take the standardized test which measures each of the Big Five personality characteristics. Then each subject was subjected to brain scans to measure specific regions in their brain. While these results will only be meaningful to a neurologist, the implications of these findings should have significance for each of us.

The Study

In a previous article on viewzone, Left Brain : Right Brain, I explained how our brains are actually two brainsconnected together by a bundle of nerves. Each side, or hemisphere, has certain characteristics for processing information. These can change depending on the dominant side, with each hemisphere controlling the opposite side of the body. That being the case, the DeYoung researchers used only right handed subjects to avoid that whole pandora’s box. The subjects were also screened for any psychiatric disorders, brain injuries or drug use — things that could alter the parts of the brain they were measuring.

The subjects were given the Revised NEO Personality Inventory to assess their personality, then a 3-T Allegra System (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) was used to acquire a high-resolution structural image — magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) — of their brains. Since people have different brain sizes, the proportions for each brain (including adjustments for sex and age) were taken into account.

For Extraversion, there was a significant association with volume in medial orbitofrontal cortex.

For Neuroticism, the two largest regions of association were in right dorsomedial PFC and in portions of the left medial temporal lobe, including posterior hippocampus, as well as portions of basal ganglia and midbrain, including globus pallidus and bilateral subthalamic nuclei. Both of these associations were negative, meaning the volume was decreased. There was an increase of volume seen bilaterally in the mod-cingulate cortex, extending to the cingulate gyrus and, in the left hemisphere, into the caudate. Additional regions not previously considered were also found to have significant increases in volume. These were the middle temporal gyrus and one in the cerebellum.

Conscientiousness was associated positively with volume in a region of lateral PFC extending across most of the left middle frontal gyrus. An unpredicted negative association with Conscientiousness was found in posterior fusiform gyrus.

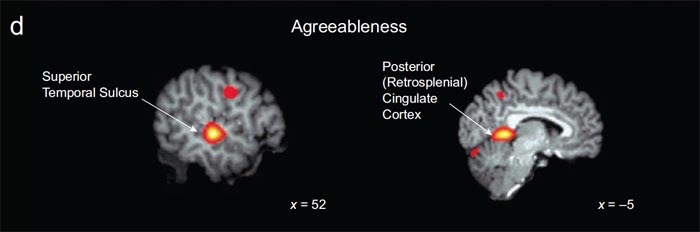

For Agreeableness, there was a significant positive association in the retrosplenial region of posterior cingulate cortex and a significant negative association in superior temporal sulcus and adjacent superior temporal gyrus. An additional, unpredicted, positive association with Agreeableness was found in fusiform gyrus.

Openness showed no significant correlation to an increase in any specific region of the brain. It is thought that all of the other characteristics contribute to the functionality of this trait.

Huh? What does it mean?

The study demonstrates that our personality is hardwired and, to some extent, not entirely subject to our free will. We react to the word in different ways, depending on the volume of specific regions of our brain. A negative, withdrawn, pessimistic personality can not easily become optimistic and outgoing merely by deciding to change — at least not instantly. But does that mean our personality cannot change? No. Indeed it can.

I asked Dr. DeYoung about this:

Dan Eden: I have a rather obvious question… which came first, the chicken or the egg. Do we assume that the various regions of the brain increased because of personality traits, or are personality traits the result of the changes to these regions of the brain?Dr. DeYoung: At some level personality must be controlled by the brain, since it’s the brain that controls behavior, emotion, cognition, and motivation, and personality is simply stable patterns in those functions. However, our study provides no evidence that the size of these particular brain regions was the initial cause of people’s personality. It is certainly possible, as you note, that engaging in extraverted behavior over a period of years led to extraverts’ having on average larger OFCs, rather than that they had the larger OFC from birth and were therefore more extraverted.

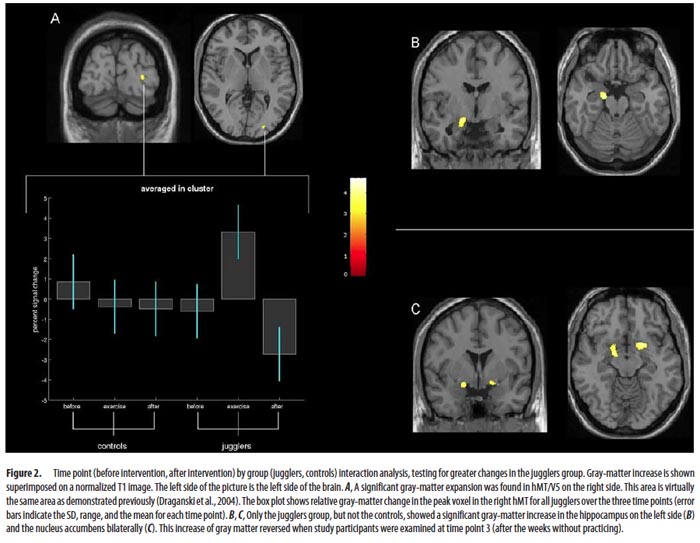

We do know that behavior can alter the structure of the brain, even over a period of weeks, as evidenced by the attached article, showing increases in cortical thickness after learning how to juggle!

So our study doesn’t answer the chicken-egg question.

While Dr. DeYoung could not answer the chicken and egg paradox, the article he sent me did. It was titled,Training-Induced Brain Structure Changes in the Elderly by Janina Boyke from The University of Hamburg. It gave me quite a bit of information that I didn’t know before.

Juggling & the Brain

When I studied biology (decades ago) I was taught that we are born with a finite number of nerve cells in our brains. I think this was drummed into our mind to persuade us not sue use illegal drugs, as they supposedly killed brain cells which would never be replaced. It turns out that this is now known to be false.

As Dr. DeYoung told me:

“First of all, it’s incorrect that neurons don’t increase in number. That’s an old and by now outdated assumption. There is neurogenesis even in adult human brains…”

To make this point, the Janina Boyke study used elderly subjects — thought least likely to be capable of regenerating neurons. A total of 93 elderly individuals of both genders were screened for any history of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, or hypertension.

The subjects were given three magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. One scan was given at the beginning of the experiment. Then, some of the volunteers of the study received three juggling balls and were instructed on how to learn a three-ball cascade. A group of control subjects received no training. After three months, the experimentsl subjects were all able to perform the skill and a second MRI was taken of both the experimental and control groups. Then three more months passed, during which time the experimental subjects did not practice juggling and lost the ability. A final MRI was then taken of all the subjects.

The subjects were given three magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. One scan was given at the beginning of the experiment. Then, some of the volunteers of the study received three juggling balls and were instructed on how to learn a three-ball cascade. A group of control subjects received no training. After three months, the experimentsl subjects were all able to perform the skill and a second MRI was taken of both the experimental and control groups. Then three more months passed, during which time the experimental subjects did not practice juggling and lost the ability. A final MRI was then taken of all the subjects.

The study found a significant increase in the brain’s gray matter in the experimental group (jugglers) following the acquisition of the training-induced juggling skill, then a decreased when the skill was lost. These changes were notable in the left frontal cortex, the cingulate cortex, the left hippocampus, and the gyrus precentral on the right side.

Here’s the BIG DEAL

The study with the elderly jugglers proves that the brain configures the neurons to process our ability to cope with the environment. This goes beyond juggling. Our brains change their hardwiring according to our behavior, eventually accommodating that behavior and making it less under the control of our conscious free will.

This means that our reaction to the world — the characteristics that make us who we are (personality) — become hardwired according to the kinds of behavior we engage in. It means that if we are in situations that allow for positive rewards from socializing, then we will become an outgoing person, full of optimism. On the contrary, if we are made to cope with fear, danger and pain, we will develop the hardwiring for being a withdrawn, pessimistic and negative person. If we are placed in a situation where we must plan ahead and maintain order, we will rise to the occasion, else we will be hardwired to lack self-discipline and be impulsive. The same is also true of compassion vs. competition.

“The one I feed the most.”

The most impressive research on the effects of behavior on the human brain was done by Daniel G. Amen, MD, in his book “Change Your Brain Change Your Life.” By meticulously alayzing brain scans from a number of patients who suffered from addiction, depression, obsessiveness, anger and impulsiveness, Dr. Amen proved beyond any doubt that these behaviors are linked to specific regions of the brain.

But that wasn’t all that Dr. Amen discovered. He noted that successful therapy could be achieved by altering the behavior long enough to allow these regions of the brain to reconfigure. This, then, is the biological definition of a “cure” for mental illness. The therapy not only involved actual changes of lifestyles or patters however. Dr. Amen discovered that the brain could not discriminate between real and imaginary behavior. Thus, imagining a behavior, such as in visualization techniques, is an effective therapeutic method for curing the illness and changing the pathology in some personalities.

There was a book that went viral in 2006 ago called The Secret. The basic premise of the book was that visualization, a kind of meditative technique where an individual conjures up visual images of a desired goal, somehow causes this goal to be achieved. The book was marketed as a means to gain “wealth, love and happiness.” Eventually the book was criticized by former believers and practitioners, with some going as far as claiming that the only people generating wealth and happiness from it are the author and the publishers. This gave visualization a bad name, and rightly so. It totally misrepresented the potentials of visualization by reinforcing negative behavior, such as greed, egocentricity and selfishness.

There was a book that went viral in 2006 ago called The Secret. The basic premise of the book was that visualization, a kind of meditative technique where an individual conjures up visual images of a desired goal, somehow causes this goal to be achieved. The book was marketed as a means to gain “wealth, love and happiness.” Eventually the book was criticized by former believers and practitioners, with some going as far as claiming that the only people generating wealth and happiness from it are the author and the publishers. This gave visualization a bad name, and rightly so. It totally misrepresented the potentials of visualization by reinforcing negative behavior, such as greed, egocentricity and selfishness.

But in truth, correct visualization is a successful method for changing personality.

Lynne McTaggart, in her book The Intention Experiment, has shown that according to electromyography (EMG) experiments, the brain does not differentiate between the thought of an action and a real action. In an study with a group of skiers, EMG discovered that when they mentally rehearsed their downhill runs, the electrical impulses sent to the muscles were the same as when physically engaged in the runs.

According to Dr. Srinivasan Pillay, a psychiatrist, brain researcher and coach, the impact of visualization on brain activation has been well-demonstrated in cases of stroke. During a stroke, because of the blood clot in an artery in the brain, blood cannot reach the area of brain that the artery once fed with oxygen and nutrients, and the tissue dies. Tissue death spreads around the area that no longer receives blood. If, however, the patient imagines moving the affected limb or limbs, brain blood flow to the affected area increases and tissue death is minimised.

According to Dr. Srinivasan Pillay, a psychiatrist, brain researcher and coach, the impact of visualization on brain activation has been well-demonstrated in cases of stroke. During a stroke, because of the blood clot in an artery in the brain, blood cannot reach the area of brain that the artery once fed with oxygen and nutrients, and the tissue dies. Tissue death spreads around the area that no longer receives blood. If, however, the patient imagines moving the affected limb or limbs, brain blood flow to the affected area increases and tissue death is minimised.

Pillay also emphasizes the importance of visualizing in the first person in order to reap the benefits. It is this which creates the experience of being in the self, thereby stimulating the neural pathways. The champion boxer Muhammed Ali was known to prepare for his fights by mentally rehearsing them in minute detail as if he were really in the ring. In The Intention Experiment, Lynne Mc Taggart says that when preparing for a fight with Joe Frazier, he would imagine “his right fist at the moment of impact on Frazier’s left eye.”

The point here is that thoughts have power. They can actually alter the structure of the brain and change our personality. While there is no “magic” that will bring wealth and happiness, the eventual changes to specific structures in our brains, brought about by visualization or meditation, will bring abou changes that improve our lives.

Oh my God! What are we doing to our kids!

Realizing that thoughts and “virtual” reality are interpreted by our brains the same way as “reality” poses the question, “What about video games?”

The US military uses real battle simulations to numb recruits to the confusion and stress of killing the enemy. In many cases, the remote infrared imaging and targeting systems in the Apache helicopter and drones is indistinguishable from a video game. In a recent viral video showing US forces accidentally killing civilians and a journalist in Iraq, you can hear the conversations between officers and the gunners. It sounds like a football game instead of an actual assassination. This is because of their training with video simulation.

Not much is different from the video games that our kids are playing with these days. They are routinely exposed to killing the “enemy” in vivid detail with blood spattering and cries of pain coming from the villains. This is immediately followed by a positive reward, either in increased points or in being allowed to continue with the game. This “learning” is, to the human brain, no different from the actual experience, according to research.

Not much is different from the video games that our kids are playing with these days. They are routinely exposed to killing the “enemy” in vivid detail with blood spattering and cries of pain coming from the villains. This is immediately followed by a positive reward, either in increased points or in being allowed to continue with the game. This “learning” is, to the human brain, no different from the actual experience, according to research.

New research by Iowa State University psychologists provides more concrete evidence of the adverse effects of violent video game exposure on the behavior of children and adolescents. The study found that even exposure to cartoonish children’s violent video games had the same short-term effects on increasing aggressive behavior as the more graphic teen (T-rated) violent games. The study tested 161 9 to 12-year-olds, and 354 college students. Each participant was randomly assigned to play either a violent or non-violent video game. “Violent” games were defined as those in which intentional harm is done to a character motivated to avoid that harm. The definition was not an indication of the graphic or gory nature of any violence depicted in a game.

The researchers selected one children’s non-violent game (“Oh No! More Lemmings!”), two children’s violent video games with happy music and cartoonish game characters (“Captain Bumper” and “Otto Matic”), and two violent T-rated video games (“Future Cop” and “Street Fighter”). For ethical reasons, the T-rated games were played only by the college-aged participants.

The participants subsequently played another computer game designed to measure aggressive behavior in which they set punishment levels in the form of noise blasts to be delivered to another person participating in the study. Additional information was also gathered on each participant’s history of violent behavior and previous violent media viewing habits.

The participants subsequently played another computer game designed to measure aggressive behavior in which they set punishment levels in the form of noise blasts to be delivered to another person participating in the study. Additional information was also gathered on each participant’s history of violent behavior and previous violent media viewing habits.

The researchers found that participants who played the violent video games — even if they were children’s games — punished their opponents with significantly more high-noise blasts than those who played the non-violent games. They also found that habitual exposure to violent media was associated with higher levels of recent violent behavior — with the newer interactive form of media violence found in video games more strongly related to violent behavior than exposure to non-interactive media violence found in television and movies.

Another study detailed in the book surveyed 189 high school students. The authors found that respondents who had more exposure to violent video games held more pro-violent attitudes, had more hostile personalities, were less forgiving, believed violence to be more typical, and behaved more aggressively in their everyday lives. The survey measured students’ violent TV, movie and video game exposure; attitudes toward violence; personality trait hostility; personality trait forgiveness; beliefs about the normality of violence; and the frequency of various verbally and physically aggressive behaviors.

The researchers were surprised that the relation to violent video games was so strong.

“We were surprised to find that exposure to violent video games was a better predictor of the students’ own violent behavior than their gender or their beliefs about violence. Although gender aggressive personality and beliefs about violence all predict aggressive and violent behavior, violent video game play still made an additional difference. We were also somewhat surprised that there was no apparent difference in the video game violence effect between boys and girls or adolescents with already aggressive attitudes.” –Distinguished Professor of Psychology Craig Anderson

Then there is this study:

Nicholas Carnagey, an Iowa State psychology instructor and research assistant, and ISU Distinguished Professor of Psychology Craig Anderson collaborated on the study with Brad Bushman, a former Iowa State psychology professor now at the University of Michigan, and Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam.

They authored a paper titled “The Effects of Video Game Violence on Physiological Desensitization to Real-Life Violence,” which was published in the current issue of the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. In this paper, the authors define desensitization to violence as “a reduction in emotion-related physiological reactivity to real violence.”

Their paper reports that past research — including their own studies — documents that exposure to violent video games increases aggressive thoughts, angry feelings, physiological arousal and aggressive behaviors, and decreases helpful behaviors. Previous studies also found that more than 85 percent of video games contain some violence, and approximately half of video games include serious violent actions.

The methodology: Their latest study tested 257 college students (124 men and 133 women) individually. After taking baseline physiological measurements on heart rate and galvanic skin response — and asking questions to control for their preference for violent video games and general aggression — participants played one of eight randomly assigned violent or non-violent video games for 20 minutes. The four violent video games were Carmageddon, Duke Nukem, Mortal Kombat or Future Cop; the non-violent games were Glider Pro, 3D Pinball, 3D Munch Man and Tetra Madness.

After playing a video game, a second set of five-minute heart rate and skin response measurements were taken. Participants were then asked to watch a 10-minute videotape of actual violent episodes taken from TV programs and commercially-released films in the following four contexts: courtroom outbursts, police confrontations, shootings and prison fights. Heart rate and skin response were monitored throughout the viewing.

The physical differences: When viewing real violence, participants who had played a violent video game experienced skin response measurements significantly lower than those who had played a non-violent video game. The participants in the violent video game group also had lower heart rates while viewing the real-life violence compared to the nonviolent video game group.

“The results demonstrate that playing violent video games, even for just 20 minutes, can cause people to become less physiologically aroused by real violence,” said Carnagey. “Participants randomly assigned to play a violent video game had relatively lower heart rates and galvanic skin responses while watching footage of people being beaten, stabbed and shot than did those randomly assigned to play nonviolent video games.“It appears that individuals who play violent video games habituate or ‘get used to’ all the violence and eventually become physiologically numb to it.”

Participants in the violent versus non-violent games conditions did not differ in heart rate or skin response at the beginning of the study, or immediately after playing their assigned game. However, their physiological reactions to the scenes of real violence did differ significantly, a result of having just played a violent or a non-violent game. The researchers also controlled for trait aggression and preference for violent video games.

The researchers’ conclusion: They conclude that the existing video game rating system, the content of much entertainment media, and the marketing of those media combine to produce “a powerful desensitization intervention on a global level.”

“It (marketing of video game media) initially is packaged in ways that are not too threatening, with cute cartoon-like characters, a total absence of blood and gore, and other features that make the overall experience a pleasant one,” said Anderson. “That arouses positive emotional reactions that are incongruent with normal negative reactions to violence. Older children consume increasingly threatening and realistic violence, but the increases are gradual and always in a way that is fun.

“In short, the modern entertainment media landscape could accurately be described as an effective systematic violence desensitization tool,” he said. “Whether modern societies want this to continue is largely a public policy question, not an exclusively scientific one.”

The researchers hope to conduct future research investigating how differences between types of entertainment — violent video games, violent TV programs and films — influence desensitization to real violence. They also hope to investigate who is most likely to become desensitized as a result of exposure to violent video games. “Several features of violent video games suggest that they may have even more pronounced effects on users than violent TV programs and films,” said Carnagey.

[“The Effects of Video Game Violence on Physiological Desensitization to Real-Life Violence,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology (July 2006).]

Let’s have a look at the Big Five personality traits again and examine where we might want to make changes.

Becoming more extroverted— Being an extrovert has many positive benefits. There are more social and occupational opportunities and it’s always healthier to mingle with others and not get too focused on yourself. To “become” the extrovert, you first have to act like one. Joining clubs and groups is a good start. Also, just going places where there are lots of people is beneficial. Your brain is looking to accommodate your behavior and will soon develop patterns that enable you to start conversations, become interested in other people’s lives and find positive stimulus from these kinds of activities.

Force yourself to start a conversation with a stranger or to feel comfortable in a crowd. Visualize yourself in a room full of people, enjoying conversation and being outgoing.

A cure for neuroticism— Having a pessimistic view of the world is a form of self-torture. Often this trait is the result of some past pain and it is fed by unreasonable fear. Knowing that there is likely a brain structure responsible for this trait, you should understand that it can be changed. Often pessimism goes along with being introverted. The solution is to begin changing the behavior to seek positive reinforcement from things that make you happy.

Happiness is an individual phenomenon. It may be a hobby or activity, a friendship — even having pets has transformed many neurotic people by distracting them from their destructive behavior and allowing their brains to reconfigure to accommodate the relationship with a cat or dog. Here is an excellent use of visualization to imagine some pleasant experience, real or remembered, that can be replayed in consciousness to establish and grow new neural pathways and shrink those contributing to negative obsessions.

Learning to be agreeable— There is a phenomenon in psychology called “Theory of Mind.” Theory of Mind is the ability to attribute mental states — beliefs, intents, desires, pretending, knowledge, etc. — to oneself and others and to understand that others have beliefs, desires and intentions that are different from one’s own. It sounds pretty simple, but many people lack this ability to some degree.

Thinking that everyone should think or feel the same as you do is a recipe for arguments and conflict when they don’t. Using your intellect and imagination, it is possible to “get inside” even the most difficult person and try to empathize with their point of view. Being agreeable is a characteristic that is taught by religions, such as Christianity and Buddhism. “Do not to others as you would have them do to you.” Often, adherence to this kind of philosophy will be enough to change your personality so that you actually become a tolerant and compassionate being.

Being Conscientious— The biggest promoter of this characteristic is military service. Being forced to adhere to a regimented schedule and to follow orders for many weeks turns almost every soldier into a model of conscientiousness. Lack of this kind of characteristic can lead to obesity (from being impulsive about food choices) and a shortened life (by making bad decisions about the future, such as smoking cigarettes or using addictive drugs). It can also cause economic failure (not following a budget) and a life full of problems. It is, in my opinion, the most difficult thing to change.

But since we now realize that conscientiousness is associated with a configuration of the brain (the prefrontal cortex) we know it can be changed. Since boot camp is a highly effective model, the same approach could be adopted to train the brain. Set a schedule for awakening, times to eat, what food to eat, and continue the organization to include making your bed, putting everything around you in its special place, making and keeping to a budget (writing down everything you spend money on) and keeping a daily log of what you have done.

Remember, this extreme behavior is to allow your behavior time to reconfigure your brain, and your personality.

Openness and Intellect— In their study, Dr. DeYoung did not find any specific region of the brain associated with either openness or intelligence. Rather, it is the ability of the balance and bandwidth of the other traits that allow for the full functioning of personality which is necessary for these characteristics. One can easily see how being socially extroverted, unafraid of life, compassionate and orderly wold contribute to an openness to aesthetics and new ideas. And with new ideas comes increased information and intellect.